A Grape Remembered: Malbec Told Through the Catena Zapata Label

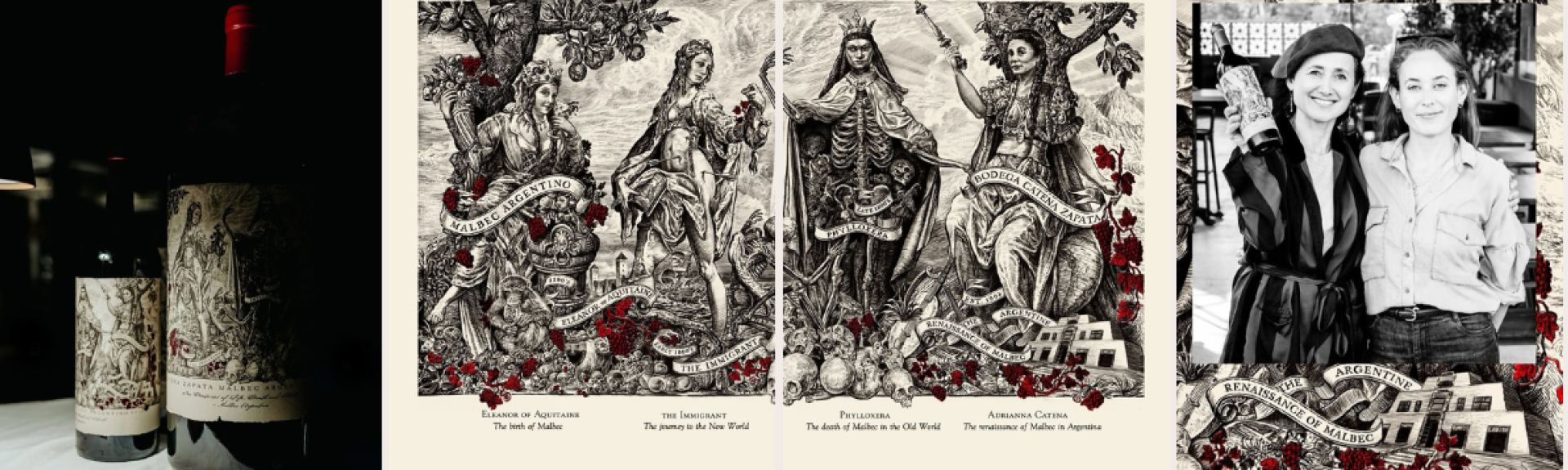

At first glance, the label for Malbec Argentino from Catena Zapata feels more like a historical document than contemporary wine packaging. Intricate line work, layered symbolism, and a deliberate sense of age encourage the reader to pause rather than pass by.

Conceived by Adrianna Catena and her sister, Laura Catena, and illustrated by Rick Shaefer, with design led by Stranger & Stranger, the label draws on Shaefer’s engraving-like style, dense with narrative and allegory, to frame Malbec as a grape shaped by time rather than trend. The four figures that populate the label each mark a pivotal chapter in the grape’s history.

The result is a visual chronicle of Malbec’s long arc of emergence, decline, and renewal, tracing its origins in France through to its modern expression in Argentina. Rather than simplifying that journey, the label embraces its complexity, positioning Malbec not as an overnight success but as a variety defined by migration, disruption, and intent.

Awarded Best Design & Packaging in Wine at The Drinks Business Awards in 2018, the label’s real achievement lies in how clearly it reminds us that a bottle can carry history, rather than merely contain wine.

The First Figure: Eleanor of Aquitaine

The presence of Eleanor of Aquitaine is not medieval ornamentation, but a deliberate signal that Malbec’s first moment of significance unfolded not in the vineyard, but in the realm of power. Born in 1122, Eleanor inherited the Duchy of Aquitaine at a time when land equated directly to influence, and wine was among its most valuable and portable assets.

Aquitaine encompassed Bordeaux and extended toward Cahors, the region most closely associated with Malbec’s early identity. When Eleanor married the future Louis VII of France at just fifteen, she did more than become queen consort; she brought Aquitaine’s wine culture firmly into the orbit of the French crown.

In the medieval world, wine did not rise on quality alone. Its fortunes were shaped by trade routes, royal favour, and political stability. Under Eleanor’s influence, the wines of southwestern France gained access to Parisian markets and, later, to England. Following the annulment of her first marriage and her union with Henry II of England, Aquitaine’s wines acquired something even more valuable than prestige: reliable export demand.

While Bordeaux would ultimately benefit most from this Anglo-French pipeline, Cahors, Malbec’s stronghold, also felt its effects. Its dark, structured wines travelled along the Lot and Garonne rivers, finding their way into royal cellars and ecclesiastical use. Long before it was formally named, Malbec became associated with depth, colour, and endurance, qualities prized in an era when wine was as much nourishment as it was pleasure.

The Second Figure: An Unknown Explorer

If Eleanor of Aquitaine represents Malbec’s proximity to power, the second figure on the label marks its true transformation. The immigrant woman stands for movement rather than lineage, for the unknown explorers, agronomists, and labourers who carried vines across oceans, often with little certainty of what would survive on the other side.

Malbec’s passage to South America was neither accidental nor straightforward. In the mid-nineteenth century, as Europe faced political upheaval and the early signs of viticultural crisis, the grape began its westward journey through scientific exchange rather than trade.

It is widely believed that Malbec first arrived in Chile in the 1840s, introduced alongside a broad range of European varieties as part of a state-led effort to modernise agriculture.

A decisive moment followed in 1853, when Malbec cuttings were brought across the Andes into Argentina by French agronomist Michel Aimé Pouget, commissioned by Domingo Faustino Sarmiento.

Then a journalist and statesman, and later President of Argentina, Sarmiento believed the country’s future depended on education, infrastructure, and agricultural reform. He championed the establishment of Quintas Normales: experimental farms and training institutions designed to accelerate national agricultural development.

Malbec arrived in Argentina not as a finished idea, but as part of this broader nation-building project.

Once planted in Mendoza, it encountered conditions unlike anything in Europe: high altitude, intense sunlight, arid soils, and irrigation drawn from Andean meltwater. What followed was not replication, but reinvention.

The grape adapted, softened, and expanded, gradually shedding its Old World associations in favour of an expression shaped by place rather than precedent. Today, Malbec World Day, celebrated each year on 17 April, marks the moment this transformation was set in motion.

The Third Figure: Phylloxera

Where the first two figures speak of power and movement, the third represents rupture. Phylloxera marks the moment when Malbec’s Old World story was not redirected, but abruptly broken.

In the late nineteenth century, the microscopic louse swept through Europe’s vineyards with devastating speed, attacking vine roots and slowly starving plants of water and nutrients. France was among the hardest hit, and Malbec’s heartland in Cahors suffered acutely.

Already marginalised by shifting trade priorities and Bordeaux’s growing dominance, Malbec found itself further diminished as vineyards were uprooted, abandoned, or replanted with varieties deemed more commercially viable.

The consequences were structural as much as agricultural. Replanting required grafting European vines onto American rootstocks, a process that favoured efficiency and uniformity. In Cahors, Malbec survived, but its role narrowed. Once valued for depth and colour, it became increasingly peripheral, its historic prominence replaced by pragmatism.

Argentina, by contrast, stood apart. While phylloxera is present, it has never taken hold with the same force or permanence. Geographic isolation, sandy soils, flood irrigation, and the natural barriers of the Andes combined to shield Argentine vineyards from the worst effects.

As a result, Malbec’s development there continued uninterrupted, ungrafted, deeply rooted, and free from the reset that reshaped European viticulture.

The Fourth Figure: The Present Day

The final figure moves Malbec from allegory to intent. Where the earlier women represent inheritance, migration, and disruption, this figure stands for authorship. She is Adrianna Catena... not as symbol, but as embodiment of Malbec’s modern chapter.

She lends her name to the Adrianna Vineyard, planted at nearly 1,500 metres above sea level in Gualtallary, Mendoza.

Established by her father, Nicolás Catena Zapata, the vineyard was conceived as an experiment rather than a certainty: an attempt to identify the coolest, most marginal sites capable of producing fine wine in Argentina. In this setting, Malbec was no longer adapting by chance but was being placed with precision.

This stage of the grape’s story is defined by inquiry. Altitude, clonal selection, soil composition, and microclimate replace survival and scale as the guiding concerns. Old vines from historic sites are studied rather than simply preserved, and expression is refined through the site rather than standardisation. Malbec, once shaped by circumstance, becomes shaped by understanding.

More Than a Label

Taken together, the four figures on the Malbec Argentino label form more than a timeline; they form a philosophy. They remind us that Malbec’s rise was never linear, nor inevitable, but shaped by power, movement, disruption, and intent.

By telling this story visually, Catena Zapata resists the simplification that often accompanies success. Instead, the label asks us to consider Malbec not as a destination reached, but as a history still in motion.

Related Articles

Bill Koch’s Grand Wine Auction: Region Performance Report

By Jonathan Stevenson

Bill Koch’s Grand Wine Auction: A Collector’s Legacy

By Jonathan Stevenson