As customers of Cult Wines, it is fair to say that you are all ‘invested’ in wine in its broadest sense as both collectors and consumers. Given this assertion, and that of most of the world is aware and concerned of our planet’s health, this report focusses on wine and its position in the global climate crisis.

It's fair to say that wine was not on the top of the list at November’s COP26 in Glasgow. Globally its carbon footprint is modest compared to many other sectors. However, wine still contributes to environmental damage and global warming by degradation of soil, reduction in biodiversity, groundwater contamination, CO2 release during fermentation, packaging, and transport. While this may sound rather glum, it’s important to face the facts in order to better understand how our wine making, buying, and drinking choices make an impact. Here, we look some of the details in these areas and at the endeavours around the world to combat the effects.

Vineyard impact of climate change

Most wine lovers have been shocked at the severe weather conditions recently and photographs of the devastating fires in Napa and, ironically, the oil burning fires in Burgundy during sub-zero temperatures. Such dramatic scenes underly the less visually obvious effects of what climate change is doing to the grapes and terroir and much has been read about some regions planting ‘new’ varieties, such as Touriga Nacional as one of the six new varieties in Bordeaux.

“Rising temperatures will suit certain varieties – Malbec and Petit Verdot are late-ripening grapes that do better in warmer vintages, and Cabernet Franc is quite disease resistant. A good approach would be to have lots of varieties planted that are budding and ripening at different times as an insurance policy,” says Lydia Harrison MW.

Industry behaviours starting to shift

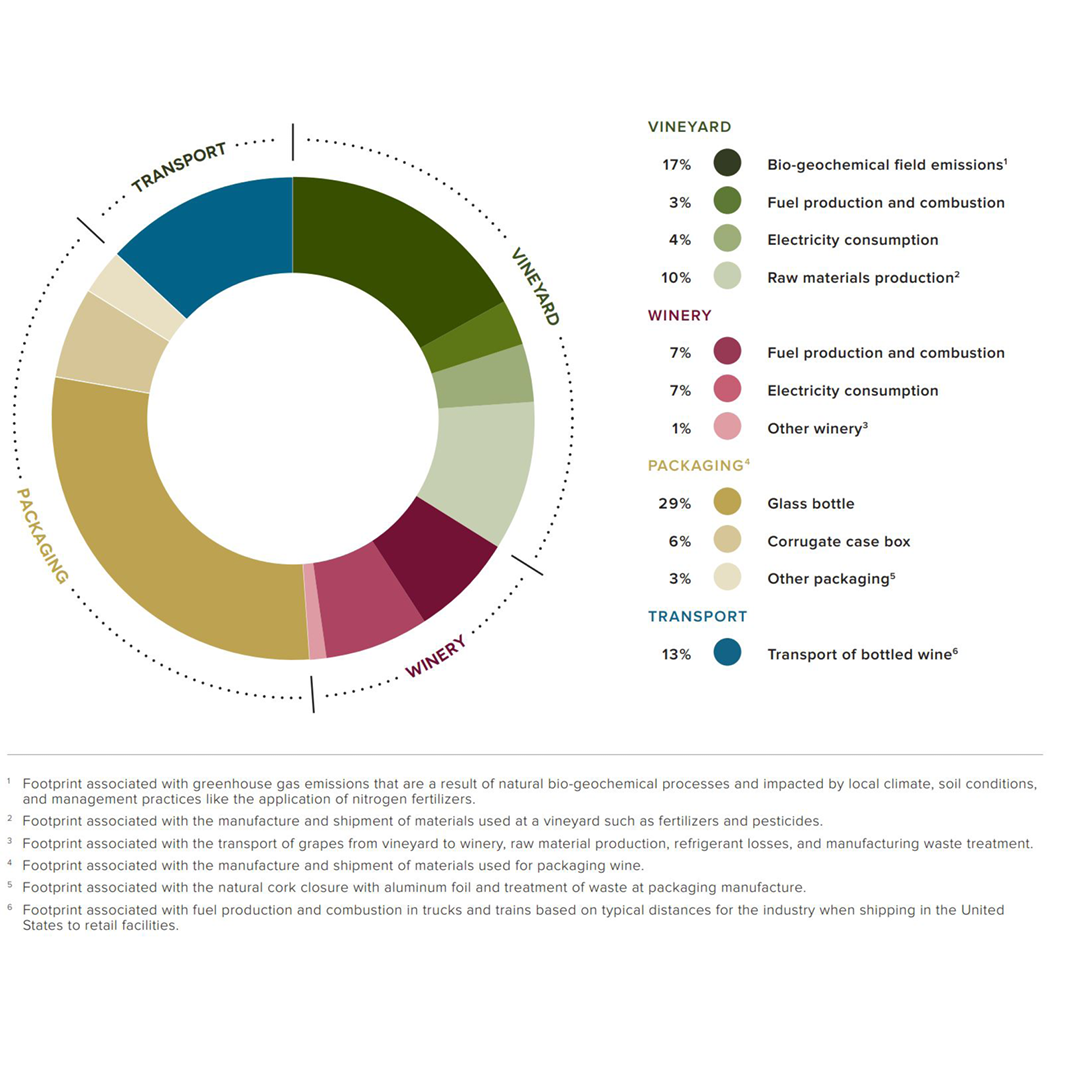

The above diagram is valuable in that rather than anecdote, opinion, or hearsay, we can see clearly just where carbon footprint emanates. A caveat is that this report was done in 2011 and was compiled by the California Wine Institute so is not an exact global representation but it is the most recent and accurate set of data available. More recently, research in Australia estimated that 68% of its carbon emission come from the use and recycling of glass bottles compared to just over half from the United States report. There will be some geographic variances, especially on transport where some countries consume most of their domestic product.

The picture is clear that these four elements - vineyard, winery, packaging and transport - are the core ‘culprits’ in carbon emissions resulting in the average bottle of wine releasing 1.28kg CO2 during its lifetime.

Human behaviour and consumption changes are critical as well as efforts by the wine industry itself. On the wine production side, there are already some efforts underway. The Porto Summit in 2019 called for actions and several leading wineries, such as Torres in Spain and Jackson Family Wines in California, are adopting less carbon-intensive methods.

However, consumer habits also need to change. Richard Bampfield MW is working other through the Sustainable Wine Roundtable (sustainablewine.co.uk) to build a common vision of sustainability and the setting of global standards. ”The younger generation care about provenance and are ready to ask awkward questions. We may soon reach a point where producers will not be able to sell their wines unless they can show they are sustainably produced,” says Bampfield.

Ed Robinson, wine buyer for the UK supermarket chain Co-op adds that ”people’s attention is shifting to what’s in the bottle and how it’s made.” The Wine Advocate in the United States has a ‘Robert Parker Green Emblem’ to ‘empower wine lovers who want to drink more sustainably’.

Many producers around the world have embraced more environmentally friendly practices from organic, biodiversity and other viticulture farming methods; some have made huge efforts to reduce CO2 output. Changes in farming methods take time to produce real results but efforts in many areas should bring positive results with time.

Other behaviours can provide far faster results if we, as consumers and retailers, change some habits. Santiago Navarro of Garcon Wines puts it very concisely: “The talk is nowhere near the action required and wine consumers are changing their habits too slowly.”

Glass bottles in focus

A major area, in fact the elephant in the room, where producers, retailers and consumers can all make some serious changes is glass. At this stage its important to say that glass has, for hundreds of years, been the ideal material for storing and ageing wine. Therefore, we are unlikely to see a quantum change for investment grade brands any time soon. What follows is more about the wine that is consumed without the need for maturation, so rest assured your collections with us will remain unaffected for many years to come.

Glass bottles and their manufacturing produce 29% of the carbon emissions in wine production, and more than 30 billion bottles of wine are produced annually. Trade estimates indicate that around 90% are consumed within weeks of purchase and a very small percentage bought for ageing. It then means that alternative packaging for ‘drinking’ wines is a major area of discussion and some activity. The traditional physical presentation of wine has always been in a glass bottle and the ceremony of opening, pouring, holding, passing and perusal of the label (let alone drinking) are powerful emotions that may require a big mind-shift in many to consider alternative packaging.

In addition to being carbon intensive, glass recycling appears to be sub optimal. Research shows that in the US only 30% of glass is recycled whereas in the UK this rises to 68%, far behind Switzerland and Scandinavia where the figure is more than 90%. So, what are the alternatives?

Trade figures for the UK show that 45% of UK wine imports arrive in bulk. The Gotham Project in the US is importing wines in ‘flexitanks’ which are siphoned off into kegs and bottled across the country. The onwards packaging options are now becoming more popular and especially with younger consumers. Bag in box (BIB) wine has been available for years but often at the lower quality end of the spectrum, but this is now changing into more premium brands. Pouches, tubes, aluminium cans, paper-based Tetra Pak and plastic bottles made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) are all becoming more popular as is the market for returnable/refillable bottles from some premium wine makers. Damien Barton of the famous Bordeaux wine family is working with a London-based wine merchant, Borough Wines, on a scheme for some of the Barton wines using returnable and refillable bottles.

There are some producers, including Nomen in Oregon, that use PET bottles in the shape of the traditional glass bottle. Others like Felton Road in New Zealand and Verget in Burgundy are taking another approach by simply reducing the weight of the bottle while still ensuring all the benefits of glass. Barton has reduced the bottle weight of Chateau Leoville and Chateau Langoa Barton wines. Jancis Robinson OBE has suggested that retailers should refuse to list wine in heavy bottles and “if consumers began boycotting absurdly heavy bottles, it would be a good start”.

Bottles often travel thousands of miles before they get to their consumption destination. Some wine-producing countries like Portugal, Germany and Greece have historically been large domestic consumers, which positively impacts transportation emissions. Some studies have suggested that the new wave of English sparkling and still wines benefit, in part, from their ‘travel friendly’ attractions as much as their quality. Politics has reared its ugly head recently in the form of trade embargos that impact, sometimes positively, carbon-based travel emissions while also creating other problems. Ultimately, many integrated factors impact wine’s carbon footprint, creating a complex picture that needs to be considered carefully.

While wine itself is not a major contributor to carbon emissions and climate change, the overall effects of global warming have made their mark on the industry. A combination of factors is at play from new forms of viticulture, packaging and consumer behaviour but together they all point to the need for us all to not only be aware of the facts but to try to understand the consequences of choices. Fine wine only represents less than 1% of the annual wine production in the world, leaving 99% as everyday ‘drinking wine’ for most. Many of us are making decisions about other products and services based on a carbon conscience to help halt the increase of damage to our planet. Our awareness and choices of what we drink have never been so important.