Wine at the Edge of the World

Wine has always thrived on adversity: thin soils, steep slopes, marginal climates. But some vineyards push that idea far beyond romantic struggle and into something closer to obsession. Places where vines survive not because conditions are ideal, but because humans refuse to accept that they cannot.

From wind-lashed Mediterranean islands to war-torn hillsides, frozen latitudes to desert sands, these are wines made at the very edge of what is possible. They are not always easy to find, sometimes impossible to visit, and often difficult to explain without looking beyond the glass.

Which is precisely why they matter.

This is winemaking at the extreme! Vineyards of folklore, and bottles that carry stories as much as flavour.

The Highest

Bodegas Colomé: Salta, Argentina

At over 3,000 metres above sea level, Colomé’s highest vineyards sit in air so thin it feels faintly surreal. The sun burns brighter, nights plunge cold without warning, and vines endure some of the most intense ultraviolet radiation on earth.

The result is Malbec of extraordinary concentration: dark, structured, yet paradoxically fresh. Skins thicken to protect the fruit, acidity remains vibrant, and ripening happens slowly despite the heat.

Colomé is not a novelty. It produces serious, age-worthy wines that challenge assumptions about altitude and elegance.

Can you visit? Yes, but only for those prepared for a demanding journey. The estate is remote, reached via long gravel mountain tracks, and altitude sickness is a genuine consideration. This is wine tourism as pilgrimage rather than weekend escape.

The Most Remote

Easter Island

Few places on earth feel more isolated than Easter Island. Rising abruptly from the Pacific, thousands of kilometres from the Chilean mainland, it is a land defined by distance and mystery.

Viticulture here is experimental and symbolic. Everything, barrels, bottles, and equipment, must be shipped in, leaving little margin for error. Pinot Noir and Chardonnay dominate, and production remains tiny, with bottles rarely leaving the island.

The wines are not polished, but they are unmistakably distinctive: an expression of survival more than luxury.

Can you visit? Yes, though wine is rarely the reason travellers come. If you encounter it, consider yourself fortunate, and don’t expect to carry much home.

The Windiest

Donnafugata: Pantelleria, Italy

Pantelleria is not so much windy as perpetually battered. Gusts whip across this volcanic island between Sicily and Tunisia with such force that vines are trained into shallow bowls carved into the earth itself.

Here, Zibibbo (Muscat of Alexandria) survives only through radical adaptation. The wines, particularly Donnafugata’s iconic Ben Ryé, are among the world’s greatest sweet wines, balancing opulence with salinity and lift.

UNESCO recognised Pantelleria’s viticulture as Intangible Cultural Heritage, a rare honour for a farming practice.

Can you visit? Yes, and it is unforgettable. Flights are limited and the landscape rugged, but the island offers one of the Mediterranean’s most distinctive wine experiences. Best avoided in high summer if you dislike wind, heat, or both.

The Most Unlikely

Bargylus: Syria

Bargylus exists where logic suggests it should not. Founded during active conflict, it produces refined wines from Syria’s coastal mountains amid instability, power shortages, and significant risk.

The wines, largely Syrah-led, alongside Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot, are elegant, restrained and unmistakably Mediterranean in character. They also remind us that wine, at its best, is about identity and continuity.

Can you visit? Not realistically at present. Bargylus is a wine encountered through intermediaries, if at all, and treated with the respect its circumstances demand.

The Most Inaccessible (For Now)

Massandra: Crimea

Massandra’s cellars house one of the world's great historic wine collections, dating back to the 19th century. Once accessible, now politically sealed, these wines mature in near silence.

They still exist. They are still cared for. But their movement, like Crimea itself, remains heavily restricted.

This is winemaking suspended in geopolitical limbo.

Can you visit? Effectively no. Even discussing access requires sensitivity. Massandra is more a symbol than a destination.

The Coldest

Olkiluoto: Finland

Not all extremes are climatic. Some are technological.

In Finland, an experimental vineyard associated with the Olkiluoto nuclear facility has attracted attention for using residual heat to support grape cultivation at an extreme latitude. Hardy varieties are cultivated in tiny quantities, producing scarce, mostly internal bottlings.

This is not romantic viticulture. It is scientific precision applied to wine: controlled temperature, controlled conditions, controlled time.

Can you visit? No. This is infrastructure, not tourism. But its existence raises fascinating questions about wine’s future in a changing climate.

The Smallest and Most Holy

Les Amis de Farinet: Valais, Switzerland

Three vines. Less than two square metres. Pinot Noir, Chasselas and Petite Arvine.

Les Amis de Farinet is the world's smallest registered vineyard, co-owned symbolically by figures including the Dalai Lama. The wine is blended with fruit from surrounding vineyards and auctioned for charity.

This is wine as a moral statement rather than an agricultural endeavour.

Can you visit? Yes, briefly. It is more a place to pause than to tour, and that restraint is the point.

The Driest

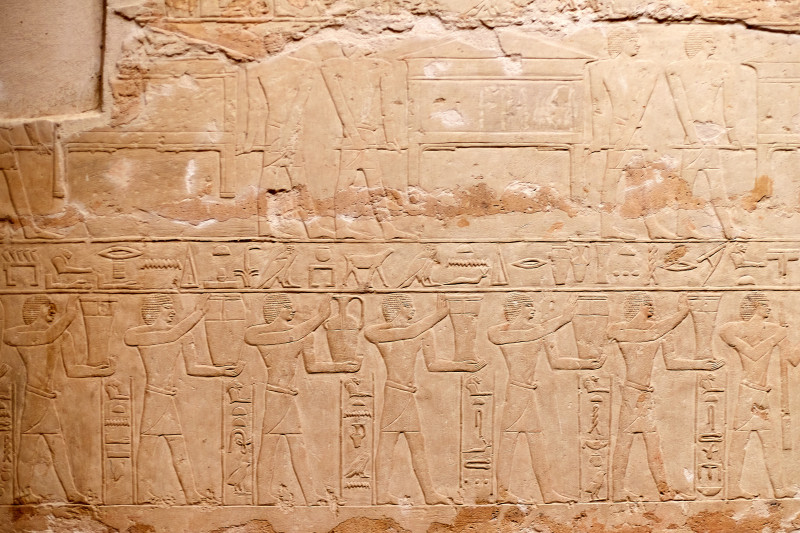

Gianaclis Wines: Sahara Fringe, Egypt

Desert viticulture on the fringes of the Sahara pushes irrigation, resilience and patience to their limits. With summer temperatures frequently exceeding 45°C, vineyards rely on deep-water access and rigorous canopy management.

The wines can be experimental and sometimes inconsistent, yet they exist improbably in one of the harshest environments imaginable.

Can you visit? Yes. Tours and tastings are possible on the road between Cairo and Alexandria. This is frontier winemaking, not polished luxury tourism.

The Wettest

Siam Winery (Monsoon Valley): Thailand

Monsoon rains, relentless humidity and disease pressure make Thailand one of the most hostile environments for wine production.

Siam Winery embraces early harvesting, hybrid varieties and constant intervention. The wines are fresh, light, easy-drinking and unapologetically modern.

Can you visit? Yes, and it is surprisingly accessible. Expect innovation rather than tradition.

The Most Urban

The 280 Project: San Francisco, USA

Vines scale garden fences, spill across backyards and root themselves into overlooked spaces between pavements and porches. The 280 Project reimagines the city itself as a vineyard, transforming private corners of San Francisco into fragments of a shared agricultural experiment.

This is not wine driven by terroir in the classical sense, but by community. Fruit is grown collectively, harvested together and vinified as a single expression of place, urban, human and unconventional.

Can you visit? Yes, but not in the traditional winery sense. There are no tasting rooms or visitor centres. Access comes through neighbourhoods, introductions and participation. You do not arrive as a guest; you arrive as part of the city.

The Oldest (Continuously Producing Region)

Areni-1: Armenia

At Areni, wine predates history. Fermentation vessels, presses and storage jars discovered in the region date back over 6,000 years.

Standing here feels less like tourism and more like archaeology of taste. Armenia’s modern wines are equally compelling: fresh, characterful and quietly world-class.

Can you visit? Yes, and you should. Armenia remains one of wine’s most underrated destinations.

The Oldest (Rediscovered Origins)

Molana: Iran

Long before France, long before wine became commerce, Persia was already fermenting grapes.

Molana links the modern revival to archaeological discoveries that push viticulture back more than 7,000 years. Residues found in ancient vessels across Iran point to one of humanity’s earliest relationships with wine: not as luxury, but as ritual and cultural glue.

The wines themselves are rarely encountered outside the region, shaped by borders, politics and history. In many ways, Molana is more about remembrance than export.

Can you visit? Not in any meaningful wine-tourism sense. Travel to Iran is possible for some nationalities, but access to vineyards is limited and rarely promoted. For most readers, Molana is a place to know about rather than to go, at least for now.

The Most Expensive

Domaine Leroy, Musigny Grand Cru

Extreme does not always mean geography. At Domaine Leroy, extremity is philosophical: microscopic yields, uncompromising selection and prices that challenge the very idea of value.

This is luxury pushed to its logical conclusion.

Can you visit? Only rarely, and by deep industry connection. The inaccessibility is part of the mystique.

Why the Edge Matters

These wines are not important simply because they are rare or difficult to obtain. They matter because, at the edge of possibility, wine stops being a product and becomes a human insistence.

A refusal to surrender to climate, conflict, isolation or time.

If you are building a 2026 bucket list, start here!

Not with the famous châteaux, but with the vineyards that should not exist, and yet, somehow, still do.

Related Articles

A 48-Hour Getaway in Champagne: The Ultimate Tasting Journey

By Paul Declerck