The Mystery of Morava: A Montenegrin Wine Discovery

Have you ever stumbled across a wine you’d never heard of, with no idea where it came from or what was inside? That’s precisely what happened to me in Montenegro one summer evening.

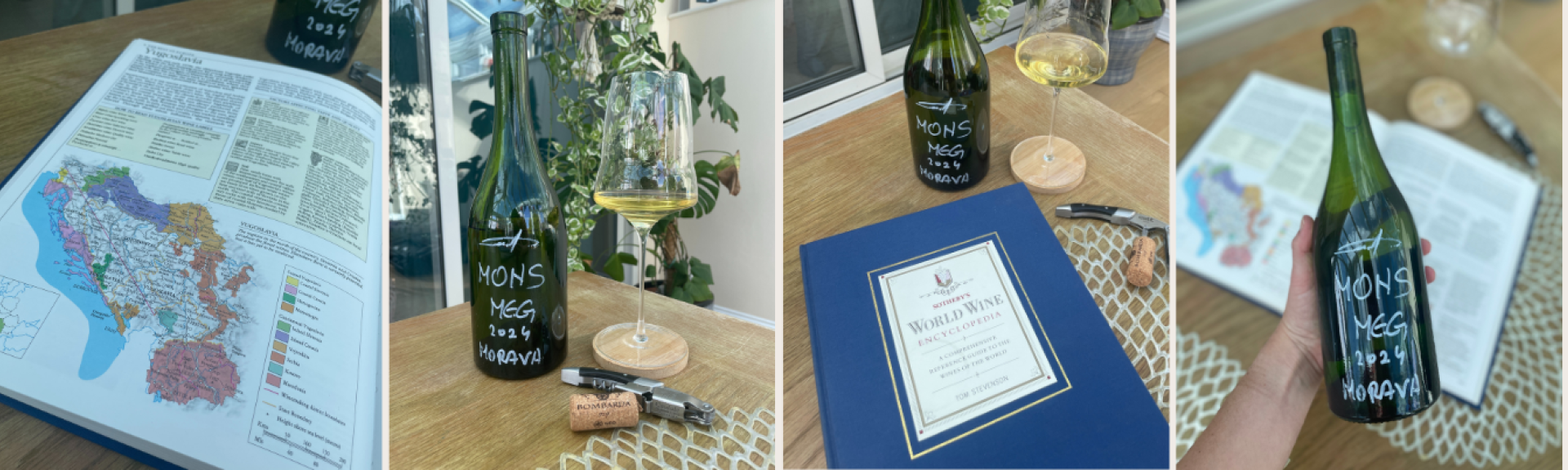

I was handed a dark green bottle, the words Mons Meg Morava 2024 scrawled across it in rough, white paint. No ornate label. No comforting reassurance of an appellation I recognised. Just a strange name and an even stranger sense of curiosity.

I had no idea what I was about to taste, and that’s where the journey began.

On holiday, there are only a few things I really need: good company, good food, and good wine. When you hit the trifecta and uncover all in one spot, that’s the dream. We ended up stumbling across a little wine bar, Old Winery Kotor, tucked into the cobblestoned streets of the old town.

A quaint bistro-style venue with alfresco tables, the sign out front read: “Support Local: You Can Do Montenegro Wine Tastings Here.” So, we grabbed a seat for what turned out to be a long, leisurely afternoon.

We enjoyed five local wines: a rosé (Pink Punk Rosé), two whites (Sauvignon Blanc Dalvina and the Mons Meg Morava that sparked this entire discovery), and two reds (Kratošija Dorian Red and Vranac/Kratošija Barut Bombarda 929). They arrived alongside cheese, olives, and the most delicious bruschetta I’ve ever tasted, topped with zucchini, prosciutto, cheese, and homemade olive oil. The food, the wine, the service, it was all a delight!

First Taste, Into the Unknown

There’s a unique thrill in opening a bottle when you have no expectations. The usual framework of price, region, and reputation is gone. All that’s left is the liquid in the glass.

In the glass, the wine shone a bright, youthful yellow, with clear legs running down the side. On the nose, fresh notes of apple, pear, and lemon were lifted by a faint whiff of petrol, a hint at the grape's parentage.

On the palate, it was crisp and tart, with high acidity. Green apple and lemon dominated, layered with hints of stone fruit. The finish lingered far longer than expected, a citrus-mineral echo that clung for more than thirty seconds. Light-bodied yet assertive, balanced around 12.5–13% alcohol, it was refreshing and characterful.

Using a structured tasting method shared with me by a friend, I scored it 84/100. Not monumental, but memorable, especially given the context of discovery.

For me, the wine carried an undeniable freshness, a bracing acidity, and a surprising aromatic lift that felt at once familiar and foreign. It was compelling. But what exactly was it? Still buzzing from the tasting, I needed answers. The word Morava on the bottle became my first clue.

Following the Clues: What Is Morava?

The name Morava turned out to be my first breadcrumb. At first, I thought it might refer to a place. Still, after some digging, I discovered that Morava is a grape variety and a relatively new one at that.

Created in Serbia, Morava is the product of modern grape breeding. Officially, it’s the result of crossing:

(Kunbarat x Traminer x Bianca) x Rhein Riesling

Of course, grape crossings are rarely straightforward, but this heritage explains a lot.

From Traminer, it inherits exotic aromatics, from Riesling, steely acidity and citrus brightness. That whiff of petrol I noticed earlier suddenly made sense, a reminder of Riesling’s influence in the grape’s DNA. And finally, from Bianca and Kunbarat, resilience and high yields. It’s a grape designed for the future: resistant to disease, cold-hardy, and capable of retaining acidity in warmer climates.

Typically, Morava is vinified as a dry white wine, though some winemakers have experimented with orange styles. Its natural profile often shows floral notes, orchard fruits, and a zesty backbone.

The name also carries geographical weight. Morava is Serbia’s great river, a lifeline running through the country. Yet here I was, drinking a Morava-based wine in Montenegro, not Serbia. That raised new questions: why would a Montenegrin producer adopt a Serbian grape?

Finding any information about this wine online was like pulling teeth and was nearly impossible. That only deepened my curiosity. And of course, the question lingered: how and where could I ever find it again? Thankfully, I had managed to bring an extra bottle home.

To understand why a Serbian grape appeared in Montenegro, I had to look further back into the days when the map looked very different.

From Yugoslavia to Montenegro: A Wine History of Shifting Borders

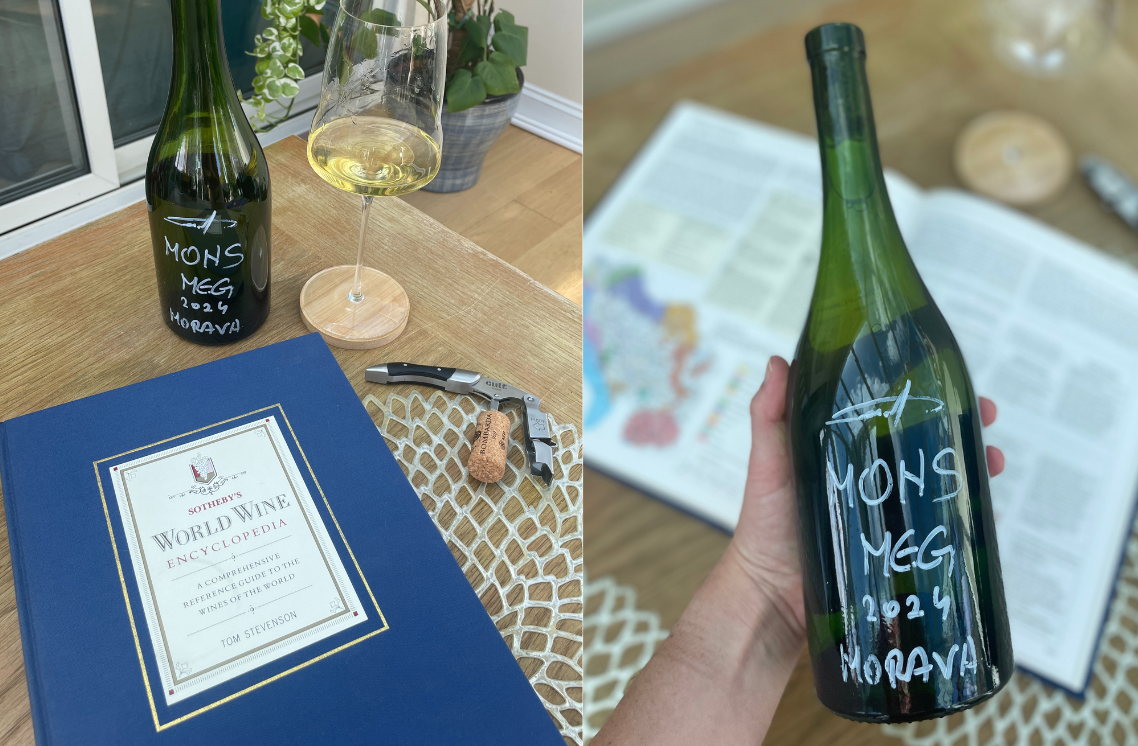

In a stroke of luck, I came across a vintage copy of Sotheby’s World Wine Encyclopedia, printed in 1988, which I had picked up at a car boot sale. Leafing through its yellowed pages, I found an entire section dedicated to the now-vanished country of Yugoslavia.

One line leapt out at me: “In the 1960s, Yugoslavia boasted one of the most modern and efficient wine industries in Europe. Sadly, this impetus was lost in the 1970s.”

With vast vineyard land, the government invested heavily, recognising the huge potential in its diverse climates and soils. But the turmoil of the early 1990s disrupted progress, leaving the wine industry struggling to find stability.

Another excerpt put it bluntly: “Lost opportunities and unfulfilled potential.”

The encyclopedia listed a dizzying array of grape varieties: indigenous names like Vranac, Kratošija, Žilavka, Plavac Mali, Prokupac, and imports like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Grüner Veltliner. It was a viticultural melting pot.

When Yugoslavia fractured in the 1990s, each newly independent country had to rediscover its wine identity. For Montenegro, two varieties emerged as national flag bearers:

- Vranac: a powerful, deeply coloured red grape, native to the region.

- Krstač: a rare indigenous white, light and crisp.

As the encyclopedia noted: “The best known vineyards of this area are those of Crmnica on the shores of Lake Skadar… wines are called Crmnicko Crno and made from Vranac grapes. Local wines are also made from Kratošija.”

This history helped explain why a Serbian grape might find itself in Montenegrin soil. The wine world of the Balkans has never been neatly divided. Grapes, traditions, and winemakers have always flowed across borders, just like the Morava River itself.

Bombarda 929, the Mystery Producer

The next step in solving the riddle of my bottle was identifying the producer. The hand-painted label gave no indication of the producer, but the cork read Bombarda 929, a name that sounded more like a piece of modern art than a winery.

After some digging, I discovered that Bombarda 929 is a boutique Montenegrin label, often associated with the Old Winery in Kotor, a venue known for showcasing Balkan wines. Their menu lists several Bombarda wines: organic cuvées, a Chardonnay called Grand Croix, and robust blends of Vranac and Kratošija.

This wasn’t a one-off experiment; it was part of a creative lineup of small-batch wines. And it wasn’t completely unknown either: at the Decanter World Wine Awards, Bombarda 929’s Crmnica 2021 was described as: “Dark fruit, violet, dried fig and prune aromatics. The palate is quite tannic and oaky with a bright beam of acidity. A very rich style.”

Another of their wines, Bombarda 929 Barut 2021, went on to win a Platinum medal at the 2023 Great American International Wine Awards. Clearly, this was a producer starting to gain recognition, even if they remain very much under the radar.

The fact that Bombarda 929 hides behind a brand name rather than a single winemaker only deepens its allure. It feels like part of the charm: a reminder that not every great wine story comes with a glossy biography or a PR campaign.

A Contrast of Scales: Plantaže vs. Boutique Experimentation

To put Bombarda 929 in context, you need to understand Plantaže, Montenegro’s wine giant. Founded in 1963, Plantaže owns over 2,300 hectares at Ćemovsko polje, one of the most extensive single vineyards in Europe. Its production, especially of Vranac, dominates Montenegro’s wine exports and defines the country’s international reputation.

Against this backdrop, Bombarda 929 represents the opposite side of Montenegrin wine: artisanal, experimental, small-scale, and enigmatic. Where Plantaže aims for consistency and volume, Bombarda 929 thrives on curiosity and surprise.

Perhaps that’s why my Mons Meg Morava 2024 felt so different. It wasn’t just a wine; it was a statement about where Montenegrin winemaking could go.

Why It Matters?

Drinking that bottle became more than just tasting wine. It became a journey. From the first sip to hours of research to flipping through a decades-old encyclopedia, I pieced together not just the identity of a grape but the story of a region in flux.

The Morava grape itself is a symbol of resilience and adaptation, bred to withstand disease and climate change, yet capable of producing wines of freshness and character.

Bombarda 929, meanwhile, embodies the spirit of modern Montenegrin winemaking: proud of tradition, yet unafraid to experiment, even if it means adopting a Serbian grape.

In the end, what stays with me is the reminder that the world of wine is still full of mysteries. Not every great discovery comes from Bordeaux châteaux or Tuscan DOCGs. Sometimes, the most memorable bottles are the ones that find you, in a tucked-away Montenegrin wine bar, with a label you can barely decipher, and a story waiting to be told.

How This Changed My Perspective

What struck me most about this experience is how it reminded me that wine isn’t only about labels, scores, or prestige, it’s about curiosity. In opening a bottle, I knew nothing about, I felt the thrill of travel itself: stepping into the unknown, allowing a place and its people to surprise me.

Montenegro, for me, went from being a dot on the Adriatic map to a living, breathing wine culture, layered with history, resilience, and experimentation. The Morava grape, born in Serbia but thriving here, symbolises the way borders shift but traditions and creativity flow freely. It made me realise that some of the most exciting wines don’t come from the famous vineyards we already know, but from tucked-away valleys and small producers willing to experiment.

That bottle taught me to approach wine with more openness. Labels and scores can guide us, but sometimes it’s the unknown bottle that becomes a passport into culture, history, and chance encounters.

Related Articles

A 48-Hour Getaway in Champagne: The Ultimate Tasting Journey

By Paul Declerck

Wine at the Edge of the World

By Christopher Cooper